The Penny Magazine

of

the

Volume VII

Issue 380

March

3, 1838

Pages 86-88

A

Week in the Isle of Portland in 1837

(From a Correspondent)

The

next half-mile brings us to a low range of coast, made up of bare hard rocks,

totally destitute of mould or vegetation, and split into "chines," so deep

and dark that I felt an involuntary shrinking as I stepped across them.

The beach is here diversified with breakers, over which the sea dashes

unceasingly. Another half-mile, and

the scene undergoes a total change - the land becomes low, with a clothing of a

warm red colour, intermingled with patches of green, caused by the thrift of our

garden borders, with its radiated flowers of pink which grows here in hard

hedgehog-like balls. The road then runs over a low iron-bound coast, broken into

every variety of angular forms, and at length terminates in a wide flat country,

level with the beach, on which a portion of the royal quarries of Kingstown are

situated. In approaching them it is

difficult to believe you are not about to visit the ruins of some ancient city.

Walls, pillars, and vast "cairns" of white stone are scattered over a

surface of two or three square miles, with what Thomson, on another subject, has

called a "regular confusion." As

these are the last quarries we shall visit, we embrace the opportunity of

stating the following particulars, which will complete their history:- The whole

amount of stone annually exported from the island is 25,000 tons, of which the

royal quarries furnish about 6,000 tons. The

number of ships employed in the trade is about eighty; and of horses on the

island 180. The market-price

of stone when it reaches London varies according to quality from 16s. To 24s.

per ton of 16 cubic feet, and pays a duty of 6s. per ton.

The

Portland ass - the donkey of the quarries, may be seen here to great advantage.

He is larger than the common English ass, is finely formed, and

remarkable for the length and set of the pastern bone, by which an elasticity is

given to the step, that renders his carriage graceful, and makes him very easy

to ride. He is usually saddled with

two large semiglobular baskets,

between which, on an elevated seat, the rider is perched.

Those used for draught, work in couples one before the other, and drag

three-quarters of a ton over rough roads with apparent ease.

Leaving

the quarries the pedestrian will take another half-mile of the shore, which

again becomes cliffy, and, gradually rising, attains a height of 340 feet.

He will here have an opportunity of estimating the force of the sea in

rough weather, as many of the blocks on the beach, of from forty to sixty tons

weight, are actually worn into immense pebbles by its violence.

Pennsylvania

Castle, the residence of the late Governor Penn, may here claim attention.

It is the only place in Portland assuming the dignity of "a seat" and

is also the only spot on which anything like a clump of trees is visible.

An old historian, speaking of this circumstance, says, "there be very

few or utterly no trees, saving the elms about the church (now gone).

There would grow more if they were there planted; yet is the isle very

bleak. This sensible remark has

been amply verified in the grounds before us.

The common sycamore will stand the severest sea breezes, and under the

shelter it affords almost any forest tree may be grown.

By surrounding his land with a ring fence of them Mr. Penn succeeded in

embosoming his house with a very agreeable variety of trees and shrubs, while

all around him was a desert. A

winding path leads us past a ruined oratory, to Bow and Arrow Castle, a noble

remnant of the days of Stephen. It

stands 300 feet above the level of the sea, on a perpendicular cliff split into

rifts like the emptied veins of a lead mine, and so loosened by age, they seem

every moment to threaten separation, and to bring the proud pile that crowns

them to destruction. Turning the

angle of the castle wall a fine view is before us.

On the left there is a range of cliff scenery from 200 to 300 feet in

height; an undercliff at its base, about 1000 feet in breadth, is covered with a

profusion of dislocated rocks amidst which many little clearance quarries may be

distinguished. To the right the sea

spreads into the distance, bounded in the horizon by the Isle of Wight, and more

nearly by the white undulating cliffs of Dorsetshire.

A walk through the ruins of the undercliff claims our first attention.

A precipitous path from the castle leads to it.

On reaching it the traveller will be surprised to see that what had

appeared at a distance to be a "waste howling wilderness," is in reality a

paradise of flowers; indeed, the undercliff and the adjacent heights constitute

together the garden of the island; The land plants of the undercliff are all of

a miniature description, or what botanists would call "starved specimens;" -

a littleness which results from the scarcity of earth, mould being formed almost

exclusively by the decomposition of the rocks.

We may here remark, that the influence of plants in the production of

colour is much overlooked, and as they affect peculiar localities, and by their

predominance give them distinct and highly characteristic aspects, deserve the

best study, both of the poet and the painter.

In no place is this more strikingly exhibited than the present.

Various species of stonecrop (Sedum) of a warm ruddy green fill

the angles of the rocks; Spurges, particularly the purple (Euphorbia Peplis),

the sea (E. Paralias), and the Portland spurge (E. Portlandica),

grow plentifully, and exhibit bright warm yellows, changing in decay to vivid

reds, which, together with the former, give great splendour to the foregrounds.

The golden samphire (Inula erithmoides), the scarlet seeds of the

flags (Irideae), and the dark green leaves of the ivy, which is sparingly

found, frequently combine with the pale red and pink flowers of various species

of cranesbills (Geraniaceae), to mantle the grey rocks with robes of

beauty. Numerous species of lichens

literally paint the rocks; the majority of them are of a blueish grey tinge,

intermingled with occasional patches of red and yellow.

Warm clusters of ferns and harts-tongues add elegance of form to the

splendour of the adjacent tints.

The

margin of the sea is also beautiful. The

sunken rocks of which the beach is composed are covered with fuci of every

degree of warm tints; and these contrast with the blue of the sea and masses of

submerged chalk. The forms and

motions of these aquatic vegetables give a gay character to the shore - some

short and paddle-formed; others long and riband shaped; hundreds of every

variety of branched and fibrous forms, and some again fine and delicate in their

structure; but all of them streaming in long undulating fields, gracefully

waving with the advancing or retreating waters, while occasionally an uprooted

conferva peeps above the surface, is driven towards the shore, dances awhile,

and sinks at length, to be again and again thrown up to the surface.

The often unheeded music of common sounds also lends its aid to the

beauties of the scene. The sea, as

it lashes over the pebbles in long sinuosities of foam, or swelling in broad

sheets bursts on the larger rocks, utters an alternate series of brisk and

hollow sounds. Linnets in happy

couples chitter in their short zig-zag flights from rook to rock, till the

echoing cliffs send back their softened merriment; the prolonged monotone of the

wheatear lends an elevated and tender emphasis to the melody of the waters,

while the blackbird in Governor Penn's shrubbery seems with his mellow pipe to

plead against the gossip of the sparrows and the loquacity of the daws in the

cliff tops.

In

returning to the castle it will be worth notice, how completely the character of

the landscape is changed by viewing it with the face to the sun; in that

position, the shadowed sides only of the rocks are seen and all appears harsh,

angular, and dismal; but turn your back to the light, and the warm sunbeams

light every thing into life and beauty. The

manner in which the various rocks decay will also deserve a passing observation.

Most of them, being compounded of different elements, decay in the order

of their coherence. In some, the soft matters vanish, leaving a curious aggregate

of crystals, bones, or shells; others shrink into singular honey-combed forms,

or resolve in straight lines, circles, or shapeless masses, which leave the

block tunnelled with large holes. Many

decay in forms so strange, that they would be difficult to describe.

We noticed one that looked like an enormous cluster of worm-casts.

The

walk on the cliffs from Bow and Arrow Castle is of a mountainous but softened

character, and terminates in a lofty conical mound, called the Vern Hill,

composed of clayey soil, and carpeted with the most delightful verdure.

This, as we have before mentioned is the Common of the island, and gives

food to a considerable number of cows; and here it is, therefore, the greatest

quantity of the fuel of the cottagers is collected.

The dung is gathered in baskets, and carried to a sunny spot, where it is

laid in rows within square borders of stones to dry, in which state it becomes a

hard, compact mass. Many compartments may be observed with 500 or more of these

cakes, with a ruddy urchin, proud of the morning's labour, turning them over

to keep them from burning.

The

road to this spot abounding with land springs is consequently thickly clothed

with vegetation, and is the place where the botany of the island may be studied

to the greatest advantage. The

following groups struck me as botanical pictures of great rarity and beauty. The white rose of Portland (Rosa spinosissima), the

Burnet or Pimpernel rose of the mainland, a plant of exquisite beauty, grows

plentifully amid the scattered rock stones, surrounded by ruddy sorrels (Rumex

acetosella et acetosa); Yellow Vetches (Vicia lutea, V. laevigata, and V.

Bythynica); Eye Bright (Euphrasia officinalis); the whole shaded by

the Tree Mallow (Lavatera arborea).

In the little spring-courses beneath them various Mints Rock and Water

Speedwells (Veronica), Forget-me-not (Myosotis palustris) of

extraordinary size, Yellow Rattle (Rhinanthus Cristi-galli), Glasswort (Salsosa

Fruticosa), and the common Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis).

In the corners of the fields clusters of the Evergreen Alkanet (Anchusa

sempervirens), and Borage (Borage officinalis) grow in unparalleled

luxuriance, and look exceedingly beautiful when flanked by the tall and

pillar-like forms of the great English melancholy Thistle (Carduus

Belemnoides). On the open

grass, and particularly on the Vern Hill, the late-flowering Orchis (Orchis

pyramidalis) is plentifully sprinkled.

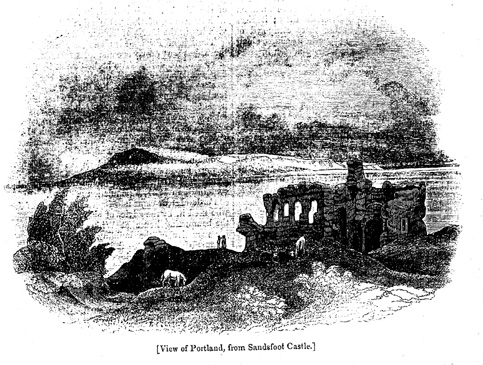

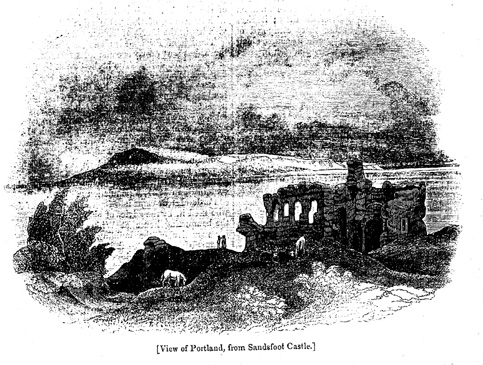

At

the foot of the Vern Hill, near the Chesil Bank, Portland Castle is situated.

This is a fort of considerable strength, and, in connection with

Sandesfoot, or Weymouth Castle, on the opposite shore, was once a very efficient

protection to the island, and the bottom of the bay of Weymouth.

It was built by Henry VIII, whose fame, and that of his family and

ministers, is thus expressed in an inscription on the wainscot of the guardroom:

"God save Kinge Henri, the VIII. of that name, and Prins Edwarde,

begottin of Queene Jane; my ladi Mari, that goodli virgin, and the ladi

Elisabeth so towardli; with the kinges honorable counselers."

From the top of the Vern Hill, during the spring

and early summer months, a phenomenon of great and rare splendour may be

observed. At those times, although

the sun exerts considerable power, the air is still comparatively cold; this is

frequently the case in so great a degree on the coast lands of England, that

immense volumes of foggy vapour are raised from the warm surface of the earth,

and immediately condensed into bright fleecy clouds. These leave the mainland, and stretching across the sea,

cover the whole of the lower parts of Portland, the higher parts remaining

meanwhile perfectly clear. On such

occasions I made it my business to leave the 'cloud-capt' valleys, and ascend as high as mother earth would

permit. On the first ascent I saw

the whole circuit of the island swaddled in what appeared to be an immense belt

of rolling clouds, over which the sun was shining brilliantly.

The sea was gone - the cliffs were immersed - and nothing was visible but

the flat top of the island, which looked like an Alpine garden floating in the

clouds. It was the most splendid

sight I had ever witnessed. I saw

this spectacle repeatedly during my stay in the island, and always found

something new to admire. Sometimes

the clouds would suddenly disperse, and then the coasts of England, the sea, and

the base of the island, would one after another appear, and would be again

immersed in clouds. At other times,

the silvery veil would slowly leave the island, and sailing gently over the

ocean, conceal first the ships, then St. Adhelm's

Head on the coast of Dorsetshire; next the Isle of Wight; and then withdrawing,

would reveal those objects in all their freshness and beauty. Occasionally, also, the cloudy canopy would not be equally

dense, or partial rents would occur in it; and then, perhaps, a ship, a house,

or a cow would be observed, and look as if floating in mid air.

The sea aids this remarkable spectacle, for although it is shut from

view, its noise is heard, and lends a feeling of mystery to the scene.