ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

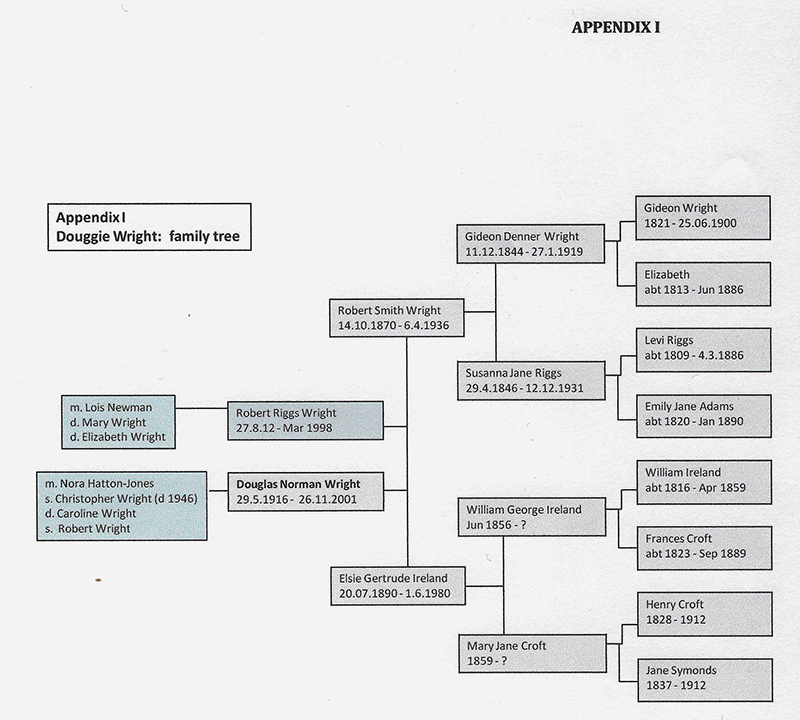

Particular thanks are due to the Dorset History Centre and to the Dorset County Museum, both in Dorchester, for their help in identifying documents of relevance to the family history back to Gideon Wright (1821 - 1900). Ancestry (at www.ancestry.co.uk) has been a particularly useful vehicle for pulling together the family tree at Appendix I that is described in this document. Thanks are due, too, to my cousin Liz Carter, to Janet Kennewell at the United Church, South Street, Dorchester, to Patrick Cooke at Athelhampton House, and to the Dorset Echo for their help in providing some of the photographs that are used to illustrate the text. Information has also been taken from a number of excellent Dorset village websites, including those for Piddlehinton, Maiden Newton and Bere Regis. The Ministry of Defence, Army Records, provided the information that underpins the period from 1940 - 1946, including the original of Douggie's Record of Service book (Army Book 439). Some details of the earlier generation of Wrights and Riggses is taken from a book "Their Excellencies" written by Canon William Joseph Wright, MA, MBE (one of Douggie's uncles) published in 1954. Aberystwyth University Library very helpfully provided access to a review of that book that was published in The Library and Book World in 1955.

Many thanks, too, are due to my wife, Jane, who has put up with me going off to work on "my project" for several months, without complaint.

INDEX

Acknowledgements

1. Introduction: and some reflections

2. Pre-history: Wrights of Dorset

3. Early life:

4. The Second World War (1939 - 1945)

5. The Firm

6. The Wrights in Dorchester

7. Family Life (1944 - 1973)

8. Family life (1974 - 2001)

APPENDICES

I. The Wright family tree

II. The family's involvement in Methodism in Dorset

III. Gideon Denner Wright and his offspring

IV. William Joseph Wright (1881 - 1954)

V. Main terms of an agreement between Gideon Denner Wright and his son Robert Smith Wright dated 28 October 1896

VI. Containerisation at Wrights of Dorset, 1960s

VII. Address given at Douggie's memorial service on 8 December 2001

DOUGLAS NORMAN WRIGHT

An Ordinary History

1. INTRODUCTION AND REFLECTIONS:

Douglas Norman Wright - known to everyone throughout his life as Douggie - was born on 29 May 1916, in Dorchester, Dorset. He was the second son of a modestly prosperous businessman, Robert Smith Wright, who ran a locally successful Provision Merchants with grocers shops in Dorchester and Weymouth.

Like 99% of us, Douggie had very little impact beyond the reach of his immediate environment, and he achieved nothing of major significance. This history is written, with a view to its completion before the 100th anniversary of his birth, simply to capture as far as possible where he came from and what he did. It tries to make use of the small amount of historical material that he left amongst his papers, mostly photographs, supplemented by information that it has been possible to glean from research online, in Dorchester and from other people. It also seeks to capture and set down relevant things that I remember being told as I grew up, while recognising that the validity of this information is susceptible both to exaggeration and/or refinement in the original telling, and to potentially highly inaccurate recall on my own part.

It is intended merely as a record for that very small number of people, mostly family, for whom it might one day be of some interest.

This history weaves together a number of different strands. There is the story of the Wright family's involvement in the 19th Century in promoting Methodism in Dorset (1). There is the story of the firm, G Wright and Son. There is the story of the very different experiences of different generations over the last 200 years. My researching of these stories, which has been fascinating in itself, has led me to reflect on a number of hugely significant changes that have occurred over this period. There is nothing very novel here; but it is interesting to recongise the way in which those changes have affected, and been effected by, our family.

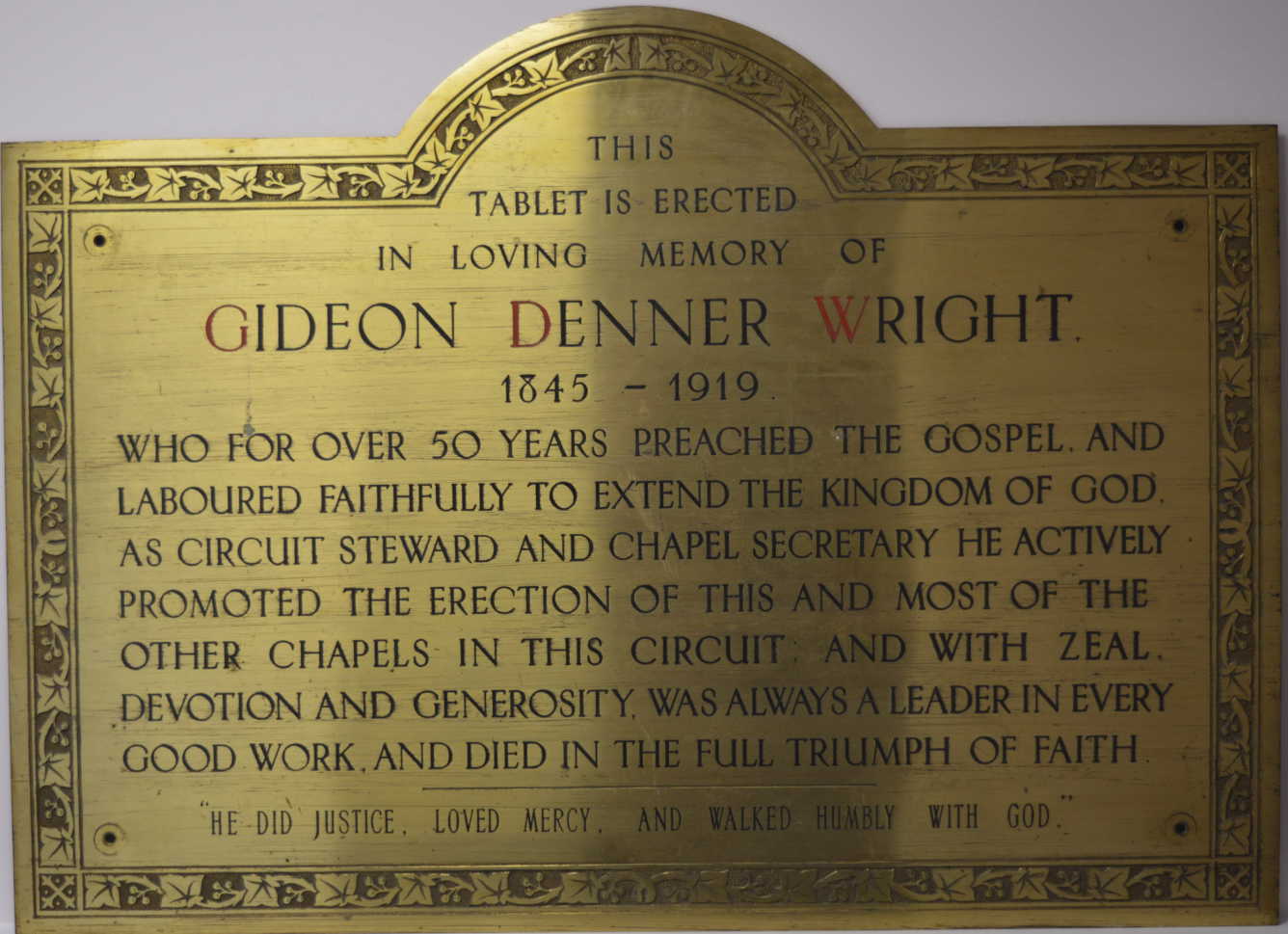

First, Methodism. Douggie's great grandfathers, Gideon Wright and Levi Riggs, were both leading lights in the Methodist church in Dorset (also known as the Primitive Methodist church and/or the Wesleyan Methodist church) throughout much of the 19th Century. Douggie's grandfather Gideon Denner Wright, who was Gideon's son and Levi Riggs's son-in-law, took up this mantle with vigour and played an important role in helping to build local chapels in several villages around Dorchester.

We should not forget that Methodists were pretty unpopular at the time. They were at odds with both the Catholic Church and with the Church of England. They had their origins very much in the Parliamentarian, puritan tradition of Oliver Cromwell. So, for example, they had no truck with the rituals and such things as the intercession of saints that are so central to the Roman Catholic faith. They also believed that anyone could preach the Gospel and lead services. It was not something that was reserved to those who had been specially qualified by church authorities to be ordained into a priesthood.

And their insistence on temperance (ie abstinence from alcohol) also strongly limited their popularity with many ordinary people!

So to be a nonconformist, or dissident, at the time when Gideon, Levi and Gideon Denner were promoting their faith was not an easy option.

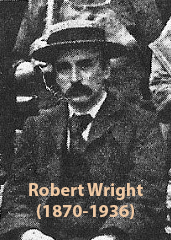

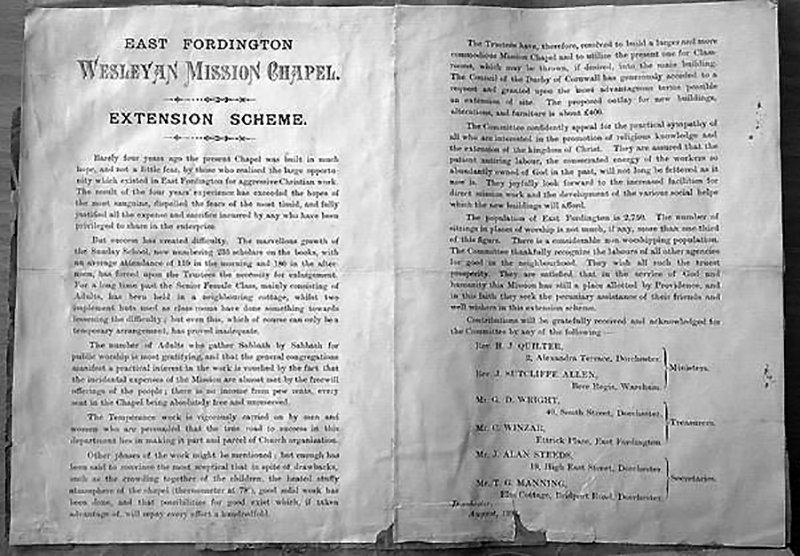

The end of the 19th Century was, it appears, something of a high point in the life of Methodism in England. It does not appear that Robert (Gideon Denner's eldest son, and Douggie's father) was particularly active in any religion. His generation (1870 - 1936) was, perhaps, the last one to feel obliged to profess a faith. It is interesting in this connection to note that most if not all of the chapels that Gideon, Levi and Gideon Denner were involved with are now private houses (Ansty, Cheselbourne, Piddletrenthide, Maiden Newton, etc) or shops (Buckland Newton) or have been demolished (Dorchester). Methodism, alongside Christianity more generally, has fallen pretty much out of fashion.

Next, the business. Gideon was clearly a very effective businessman. The son of a labourer, he pulled himself up by his bootstraps (no pun intended) to go from being a travelling shoesmith at the age of 20 in 1841 to owning his own substantial grocery and pork butchery by his early 50s. He handed on a thriving business to his son, Gideon Denner. Gideon Denner in turn brought his eldest son, Robert, and his youngest son, Denner, into partnership in the business. Douggie joined the business on leaving school, and his elder brother Robert (Robin) joined the business after the Second World War. There was, however, never any thought that I or my sister or cousins would go into the business and we were given no encouragement to think that we might do so. That may have been for any number of reasons. But it is a fact that, by the time I had reached an age at which I would have been looking for work, the Wright family business in any case no longer existed.

It is perhaps indicative of the way that commerce changed during the 1960s/70s that Douggie and Robin merged G Wright and Son with another business on the Isle of Wight, took the combined business to the London Stock Exchange, and then shortly afterwards sold their interests in it. That was probably a wise thing to do. And the period saw the closure of a large number of local Dorchester businesses, including Tilleys (cars and bicycles), Parsons (tea and coffee merchants), Ricardos (builders), and Lott and Walne (foundry). In practice, few if any of these businesses were generating enough income to support the engagement of another generation of the family. Consolidations and takeovers were very much the order of the day. Eldridge Pope's brewery business lasted longer than most, but still succumbed finally in 2010. A few other small local businesses such as Goulds department store, Lings (printers) and the professional accountancy firm of Edwards and Keeping (though in the last case now with no active family members) still survive, but they are the exception, rather than the rule. Douggie and Robin's generation was the one that saw the near-extinction of the family business as such, and its replacement with the here-today-hopefully-bought-out-very-profitably-tomorrow culture of the Thatcherite entrepreneurial start up.

Third, generational expectations:

-

Robert's generation went through the First World War. Douggie and Robin's generation went through the Second World War. My generation and my children's generation have been remarkably fortunate in being the first ever not to have known or been involved in active conflict of one kind or another. So far.

In Robert's generation, and in those before him, most people went to work as soon as they were physically capable of doing so. Robin and Douggie's generation went to work after a relatively rounded and extensive education up to at least the age of 15, leaving at the School Certificate stage. I was only the second Wright (after Douggie's uncle William Joseph) to go to university, and even then alone amongst my generation in being lucky enough to do so - as much, I suspect, because I was the only boy as because of anything to do with ability or aptitude. My children, and my cousins' children, all went to university. The family lived for over two centuries and for four generations in Dorset, in Dorchester or Piddletrenthide. They worked in Dorchester. My generation started to move away, although the fact that Douggie and Robin stayed put meant that we all had connections back to the county. As it happens, my cousins and I have all come back to Dorset (or very close thereto) in our retirement. For my own part, I can only say that I feel a very strong connection to the county, and I am very happy to be back in Dorset after spending most of my life away. I feel strangely that I belong here. The next generation, however, will feel very different loyalties, and will likely have very little to connect them to the county of their forefathers.

It is also interesting to reflect on the nature of the main characters in this story.

-

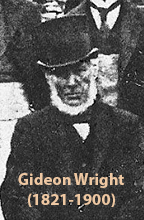

Gideon initiated the family business. A staunch Methodist, he played a significant role in developing the Methodist church in North Dorset. By the time of his death in 1900, he was a wealthy man, and something of a pillar of the community.

Gideon Denner played, if anything, an even more significant role in the Methodist church, alongside his father-in-law, Levi Riggs. He is directly connected with the building of more than half a dozen chapels in Dorchester and in villages as far flung as Piddletrenthide, Maiden Newton, Cheselbourne and Bere Regis. This is no mean feat when one remembers that, at the time, travel between these places was on foot, on horseback or by horse-drawn carriage. At the same time, he ran and developed a highly prosperous business. And he still found the opportunity to father 14 children!

Robert is much more difficult to pin down. He lived at home with his parents until he was 40, working under his father in the family business. He then married someone who by the standards of the time would have been regarded as being very much beneath him - although she gave the impression at least later in life that she'd been born from the outset used to a life of upper middle class comfort. Did he have to stand up to his father over this? Or were Gideon Denner and Susanna quietly relieved that at last he'd moved out?

Robert became one of about a dozen Borough Magistrates sometime in his 50s, in which role he was a colleague of Thomas Hardy OM. Robert was still a Justice of the Peace in 1931. But apart from these few thin facts that it is possible to trace at this distance , he seems to have slipped through life without much touching the sides, leaving very little by way of a trace. There is no evidence, either actual or anecdotal, of his having actively promoted Methodism to his own children (although Douggie's brother Robin became a mainstay of the Church of England in Piddletrenthide). There is no sign that he did much if anything to grow or develop the business, leaving a shop and yard in High East Street much as he'd inherited it from his father, 15 years earlier - albeit that his estate was twice the value of his father's.

Of Douggie we of course know a good deal more, primarily because we have firsthand accounts of what he did. He seems to have enjoyed his business life - one gets the sense that innovating things, in particular, was fun for him - and it seems to have given him a decent standard of living, even if he never managed to make much money out of it. He was ahead of his time in not retiring until he was well into his 70s. After his retirement he left Dorchester and moved to Marnhull, where he threw himself enthusiastically and generously into supporting local charitable efforts.

One thing in particular that strikes me as a result of this research is that the family business came full circle in just four generations. From nothing, to relative prosperity, to nothing again. That's no-one's fault as such; it's merely a consequence of history and circumstance. But it's an interesting fact.

Notes:-

(1) Much of the most interesting historical material, both about family members and about their role in promoting Methodism in Dorset, is in the Appendices to the main text2. PRE-HISTORY: WRIGHTS OF DORSET [Link to more information about Gideon Wright's father John Wright (1785-1861) on the OPC website]

The core family tree for the Wrights is at Appendix I. Douggie's great grandfather, Gideon Wright, was born in 1821, the son of a labourer, John Wright and his wife Elizabeth . There appears also to have been a daughter, Ellen, born in around 1826, who appears in the 1841 Census. But it is not clear whether she survived into adulthood, or if she did, what happened to her.

In 1841, at the age of 20, Gideon was a journeyman shoemaker, living with his parents in Back South Street, Dorchester. He would have earned his living travelling around the town and the local area mending and making shoes. Yet he clearly managed to improve himself. By 1852 he was listed in Slater's Directory for the town under the heading of "Shopkeepers and Dealers in Groceries and Sundries" and by the 1861 Census he was able to describe himself as a Master Grocer.

Gideon's wife Elizabeth was 8 or 9 years older than him. On 11 December 1844, Elizabeth gave birth in Dorchester to Douggie's grandfather, Gideon Denner Wright (2). She survived to the age of around 65, dying in 1886. At the age of 68, Gideon remarried. Mary Battiscombe was a lace cleaner from London aged 63. They lived together for 11 years until Gideon died at the age of 79 in 1900. Mary died in 1913 at the age of 87.

Gideon Denner, as the first (and, as it turned out, the only) son, would have started in the family business from about the age of 14, ie in around 1858, or possibly earlier (there being no compulsory school leaving age until the Elementary Education Act of 1880 first introduced one). This is consistent with his description in the 1861 Census, when Gideon Denner then aged 17 was living at home with his parents at 17-18 Grove Buildings in Dorchester, and his occupation was given as a Grocer's Assistant. Eight years later, on 15 July 1869 at the age of 25, he married Susanna Riggs at Cheselbourne Church. Born in Dewlish, Dorset on 29 April 1846, she was a couple of years younger than him.

Susanna's father (Douggie's great grandfather), Levi Riggs, was a successful farmer. In 1871 he was employing 8 men and 4 boys at his farm in Cheselbourne. From 1885 to 1922 he and his son Joseph Adams Riggs also tenanted Manor Farm at Piddlehinton (3). William Wright (one of Douggie's uncles), writing in about 1951 in his book "Their Excellencies" (4), described him thus:

"My grandfather was a Dorset farmer, very hard working, and to the modern mind he may seem to have lived a very narrow life. Nevertheless, he lived intensively, and he achieved tasks and purposes which today seem remarkable. He would ride 50 miles to Bristol in order to attend the Methodist Synod, and he saw nothing incongruous in acting as a churchwarden and attending service at the parish church. His life was as straight as the shortest distance between two points and the word "compromise" was one which he could never act upon."

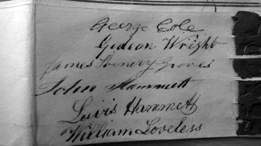

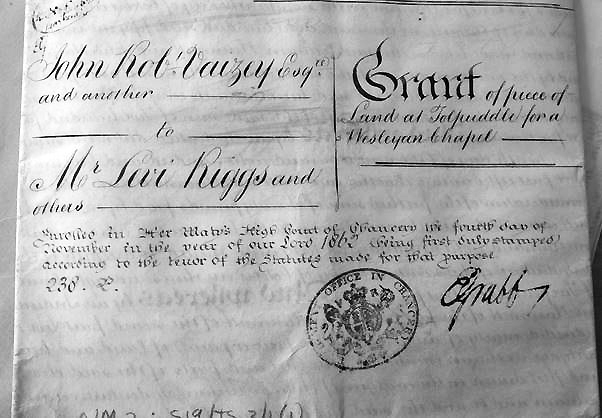

Levi Riggs was also a leading member of the Wesleyan branch of the Methodist Church, alongside Gideon and Gideon Denner. In the 1871 Census, Gideon Denner is described as being a grocer and provision merchant and a "Methodist Local Preacher". Levi, Gideon Denner and Gideon are named amongst the trustees of a number of Methodist Churches in Dorset including at various times Dorchester, Tolpuddle and Maiden Newton, in each of which they had played a part in acquiring the relevant land and building of Wesleyan churches on it. Further details of their leading involvement in the Methodist Church in Dorset is at Appendix II. Levi Riggs died on 4 October 1886.

-

Side Note: One of Levi's sons, also called Levi, farmed most of his life in Piddlehinton and became a noted breeder of Jersey cattle. He was killed in 1918 when his coat caught in some farm machinery (5)

On 14 October 1870, Susanna gave birth to Robert Smith Wright, Douggie's father, at their house at Grove Cottage, Millers Close, Dorchester.

Robert was the first of 14 children - eight boys and six girls - to whom Susanna gave birth over the next 20 years, 12 of whom survived childhood. Surprisingly, notwithstanding the strain this must have placed on her, Susanna survived until 12 December 1931 when she died at the age of 85. As was usual at the time, the older children (particularly daughters) would have taken over much of the care of the younger ones. There is a story that on one occasion, Alfred Denner (their youngest son, known as Denner, born in 1890) took his mother the morning paper to read. As she thanked him she added the comment "And who's little boy are you, then?".

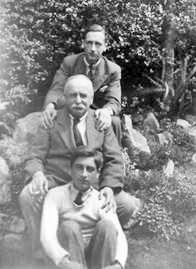

Individual pictures of Robert, his father and his grandfather, taken from a group photo in the late 1890s of the directors and staff of G Wright and Son (shown in the section on The Firm, below) are below.

William Wright was the third of the eight boys, born 11 years after Douggie's father, Robert. William's book talks of his childhood at home in the following terms:

"My father, christened Gideon, lived up to his name and he was eloquent in both words and deeds. He had twelve (6) children, and the task of providing for such a large family did not prevent him from driving eight, ten and even fifteen miles on a Sunday to preach in some country church.

"My mother was that miracle of love and sacrifice to be found in so many Christian homes. The sacrifices involved in caring for her large family were taken as a matter of course, and there can be no doubt that her patience and lasing affection had their inspiration in her faith which was always equal to every situation, no matter how trying it happened to be.

"Family prayers were held morning and evening, and Sunday always ended with Jackson's Te Deum, one of my sisters playing the organ and another the piano. As a boy, I felt that this was rather too much and I feared that the sound of the singing would penetrate to the nearby school which we attended, and, in fact, this frequently happened."

Pictures of Robert, taken when he was around 20 and around 30 are shown below.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Robert probably left school and joined the family business in his early-teens. As discussed in more detail later, at the age of 26 in October 1896 he was taken into a formal legal partnership with his father, Gideon Denner. On 11 August 1910, while still living with his parents over the shop in High East Street, Dorchester, Robert married Elsie Gertrude Ireland at Broadstone Church near Poole. Robert was 40, quite old for a first marriage, and a relatively prosperous businessman. Elsie was 20, by all accounts a beauty, and was the daughter of a gardener and a laundress, with some acknowledged Romany blood on at least her mother's side if not both sides of the family. It was hardly a marriage of equals; but it was doubtless one that suited both very well. Robert and Elsie's first son Robert Riggs Wright (known throughout his life as Robin) was born on 27 August 1912. Then in 1916, on 29 May, Elsie gave birth to their second son Douglas Norman Wright (Douggie).

Notes:-

(2) referred to throughout this document as Gideon Denner, to distinguish him from his father Gideon(3) The Story of Piddlehinton, Dorset Books, 1990, p 11.

(4) pub E Backus, Leicester, 1954

(5) from documents held at Dewlish Mill, with acknowledgement to Mandy and David Hawkins.See also an article in the Western Gazette of Friday 5 July 1918. It is also recorded that one George Bollen, who was 92 in 1970 and had been custodian of the Methodist Chapel, confirmed this story.

(6) In fact 14. We know that one boy, George Levi, died young; and presumably one other, probably the third daughter, Margaret.

(7) Currently in the possession of Rob Wright

At the time of Douggie's birth, Robert and Elsie were living at a house ("Elsinore") at Number 1, Dagmar Road, Dorchester. Robert was at this time running the family business and was a minor local dignitary, having inter alia become a Borough Magistrate of the town Corporation by 1915, alongside other local figures including the author Thomas Hardy OM (8).

Not much is recorded about Douggie's early life. There are just two blurred baby photos (below), neither of them very flattering.

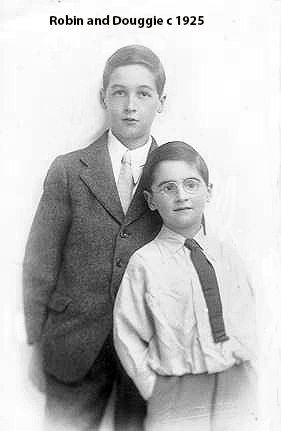

It was expected that the children of such a relatively prosperous business family would be educated privately. Nothing is known of where Robin or Douggie went initially to school. But by the time they were in their teens, Robin was boarding at Blundells School in Tiverton, Devon. Douggie was at Dorchester Grammar School from 1925 - 1928 and then at Weymouth College (later to become Weymouth Grammar School) from 1928 - 1932. He passed his School Certificate (the equivalent of GCSEs) in 1931.

Douggie had been born with extropia, a reverse (ie outward looking) squint also known as a divergent strabismus, which meant that he was unable to bring his eyes to converge properly on a point. [Interestingly, close examination of the original photographs of his father on previous pages suggests that he may have suffered from the same condition.] Douggie had at least one operation as a child on the muscles around his eyes to try to correct this problem, but it was unsuccessful. As a result, throughout his life, he had double vision of anything in the centre of his field of view. He compensated for this to some extent by mentally blocking the image from one eye or the other, but this gave him only monocular vision (ie with no sense of perspective). It was very tiring and it meant that, for example, he was never able to play ball games (as he couldn't judge how fast things were approaching him). This must have made him something of an outsider amongst his contemporaries at school.

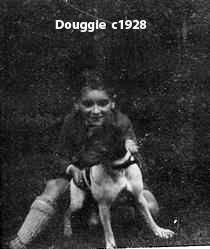

There are only a few photographs from Douggie's later childhood. In the first, where he appears to be around 8 or 9 years old (ie in around 1925), he is with his brother Robin. In the last two, he is pictured with his parents (Robert and Elsie) and Robin. The final picture in this group shows Douggie's mother Elsie from around the same time.

Elsie ca. 1932

Robert died on 6 April 1936 in Yeovil Hospital. The story passed down is that he had a heart attack when he was involved in a road accident while passenger in a car that Douggie was driving. If that is so, it must have been a great personal shock for Douggie who was well known to have been particularly fond of his father.

Notes:-

(8) Kelly's Directory, 19154. THE SECOND WORLD WAR (1939-1945)

Douggie enlisted in the Royal Artillery at Exeter as a Gunner (ie Private) on 18 July 1940. He was transferred to the Pembroke Heavy Regiment in Milford Haven on 15 August and then to the Coastal Artillery School at Llandudno on 24 November. In the meantime, he applied for a Commission.

On 19 September 1940, he was interviewed by a Board chaired by a Major H C Gould. The Board report described his Military Character as "very good". His Power of Leadership was said to be "Average - but with experience he should attain a higher standard". And the overall assessment said that he was "A quiet mannered boy [comment: aged 24!] who with an Officer Training Course behind him should make an officer well up to the average".

Following this not entirely glowing assessment, he was posted as an Officer Cadet to the Officer Cadet Training Unit in Plymouth on 27 September 1940, and on graduating from the course on 20 December 1940, his Commanding Officer Major G Barnett signed his release from the ranks for the purpose of being appointed to a Commission. The paperwork says that his Military Conduct had been "Very Good during his 6 months service". It noted that he had "Qualified by his conduct to have received an award of Exemplary for military conduct", but that he was "ineligible [for an Exemplary marking] because he has not completed 2 years service". The notes went on to describe him as:

"Hardworking, reliable and honest. Can be thoroughly recommended for a position of trust. Well educated, intelligent and self-reliant".

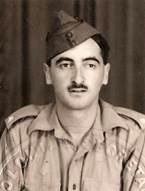

On Christmas Eve in 1940 he was posted back to Llandudno as a newly appointed 2nd Lieutenant, and then on to Coastal Artillery Sections in Newhaven and Brighton and the Searchlight Section at Worthing. A photograph from about this time, as a 2nd Lieut, is shown below. It is more than likely that it was in this period that he first met Nora Hatton-Jones, who lived in and around Bognor Regis, and whom he was to marry in 1944.

In early November 1941, he was posted to the RA Depot at Woolwich in London. Then, on 2 December 1941, he embarked for Gibraltar. He told the story that he had embarked from Gibraltar to go to Singapore but that, when Singapore fell on 15 February 1942, his ship returned to Gibraltar where in the end he was to spend much of the rest of the war lobbing shells onto German positions in North Africa.

In early November 1941, he was posted to the RA Depot at Woolwich in London. Then, on 2 December 1941, he embarked for Gibraltar. He told the story that he had embarked from Gibraltar to go to Singapore but that, when Singapore fell on 15 February 1942, his ship returned to Gibraltar where in the end he was to spend much of the rest of the war lobbing shells onto German positions in North Africa.

On 21 June 1942 he was promoted to Lieutenant. He became an Acting Captain on 1 December 1942 and a Temporary Captain on 1 March 1943. While still in the substantive rank of Lieutenant, he was appointed an Acting Major with effect from 10 February 1944.

The photograph below shows his battery on Gibraltar in 1943, with Douggie seated centre.

Amongst his papers were some documents relating to this period. Photos from these documents are shown below. One, dated 4 July 1942, acted as an Identity Card for travel from Gibraltar into Spain. Others, dated 20 and 22 April 1943, relate to a visit Douggie was to make on government business from Gibraltar to Tangiers. It is presumably from this visit to Tangiers that the story arose of a particularly lucky escape. Douggie had been met by a car on his disembarkation from the ship in the harbour in Tangiers. He told the driver that he wanted to stretch his legs, and would walk to the end of the pier where the driver could pick him up. As it drove down the pier, the car exploded either from a bomb or from being hit by a shell, and the driver was killed outright. Douggie survived without a scratch.

Douggie: July 1942 Douggie: April 1943

All his time in Gibraltar, Douggie had been trying to secure a transfer from the Royal Artillery to the Infantry, specifically to the Dorsetshire Regiment. He eventually managed to achieve this in early 1944. On 18 March 1944, he arrived back in the UK and, after 3 weeks disembarkation leave, he went back to Woolwich. By this time he was a Lieutenant again, having had to relinquish his more senior acting and temporary ranks on leaving Gibraltar. He was admitted to the Royal Masonic Hospital for an unspecified reason on 25 April 1944 but was out again and posted to 522 Coastal Regiment on Portland by 10 May 1944. In October 1944 he got married and was granted 10 days leave before returning to Portland. He then went on an infantry conversion course in Dunbar from 28 November 1944 to 26 January 1945. And then on 28 January 1945, he finally achieved his ambition to transfer to the Dorsets.

Nothing is known of what he got up to most of that year. The Germans surrendered in the first week of May. But on 21 November 1945, he embarked at Dover with the 1st Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment to join the British Army on the Rhine. He was posted with the First Battalion, Dorsets, first to Oerrel near Hamburg to join in the clearing up after the war, and then in March 1946 to Berlin. He never really talked about this time, except to say how devastated the infrastructure was in Berlin, to the extent that it was cheaper to brush ones teeth in champagne than in water. On 5 May 1946 he joined the 5th Battalion Dorsets, prior to being demobbed on 28 May 1946, which was almost certainly coincidentally the day before his thirtieth birthday. His record book shows that he was authorised by his commanding officer at Aldershot the day after to exhange 640 Deutschmarks for sterling, the final sign off of his engagement in the Army.

That said, Douggie's Record of Service book (AB439) has a note scribbled in pencil inside the back cover. This says: "20th September [no year], Dorset Dinner, Dorchester Hotel, Too drunk to know". It is signed by a Bill Ridley. Hmmm ....

The first description of Gideon Wright (the original "G" of G Wright and Son) as a grocer is to be found in Slater's Directory for 1852, where he is listed under the heading " Shopkeepers and Dealers in Groceries and Sundries". By the 1861 census, he was describing himself as a Master Grocer, with premises at 17-18 Grove Buildings, West Fordington. Fordington at the time was a parish which extended in a crescent from the military barracks at Poundbury to the West of the town all the way around to the area around St George's Church, the parish church, to the East of the town. Grove Buildings no longer exist, although the name carries on in The Grove which constitutes part of the main road out of town to the North from the Top o' Town. In 1861, Gideon Denner, aged 17, was living with his parents at Grove Buildings and was described as a Grocer's Assistant.

By the 1871 Census, Gideon had expanded the business and was living in 17-19 Grove Buildings. He is listed as a Grocer and Provision Merchant employing 3 hands. Gideon Denner, newly married, had moved round the corner to Grove Cottage at 1 Miller's Close. Miller's Close still exists as a road but is now part of a large industrial estate at the bottom of the Grove. Gideon Denner was also by now described as a Grocer and Provision Merchant.

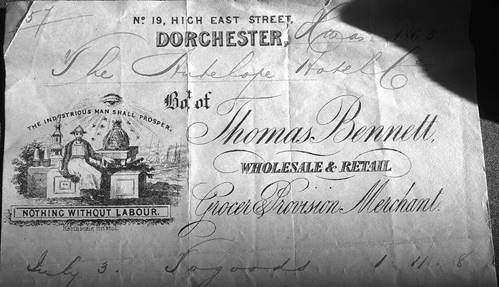

On 11 October 1873, Gideon entered into a contract (9) with Thomas Bennett whereby G Wright and Son (the first time the name appears as such) would buy Bennett's business - described as consisting of "several trades or businesses of a Grocer, Provision Merchant and Pork Butcher" - at number 19 High East Street, Dorchester. [The photograph below shows a copy of an earlier account sent by Thomas Bennett to the Antelope Hotel, dated Xmas 1865 (10).] The purchase of the business included all "stock in trade, utensils, implements, articles and materials and effects of every kind", which Gideon bought for the sum of £940 (equivalent to about £96,000 at 2016 prices). By the same agreement, Gideon also undertook to rent the property, which included the shop at 19 High East Street together with stables and other buildings in Bell Street (now Icen Way), for 21 years at a rent of £100 a year.

As a result of this agreement, the 1881 Census shows Gideon and Ellen for the first time at 19 High East Street, Dorchester where they were living above the shop. By this time, Gideon was employing 12 men. Gideon Denner had moved to Trinity Street where he was living with his wife Susanna, seven children (including Robert, then aged 11), one of Susanna's sisters (Emily Jane Riggs, aged 32) and two servants.

In the course of the 1880s, Robert left school and joined the family business. The picture below shows the three generations of Wrights (L-R Gideon Denner, Gideon and Robert) with their staff. It must have been taken around 1890 - 1895. It is likely to have been taken in the stable yard behind 19 High East Street on what is now known as Icen Way. It shows the twelve men and a lad who were presumably employed by the firm at the time.

© Picture kind permission of Robert Wright

By 1889, Gideon - then aged 68 - was contemplating retirement. On 2 October 1889, he and Gideon Denner signed a formal agreement bringing Gideon's involvement in the business to an end. This noted that they had "for many years carried on business in Dorchester, Weymouth and Melcombe Regis" and that they had agreed "to end the co-partnership" in exchange for Gideon Denner agreeing to pay Gideon the sum of £100 a year for the rest of his life. The agreement went on to note that "in pursuit of the said arrangement and in consideration of the natural love and affection which the said Gideon Wright has for his son Gideon Denner Wright", Gideon assigned his whole share in the business to Gideon Denner. Explicitly excluded from the agreement, however, were a number of assets which Gideon continued to retain, including "his share of certain premises situate in West Walks, Dorchester; his share of Sydling Mills; a debt due from Ballam & Son on the security of their promissary note; a share in a certain policy on the life of J A Riggs(11); and his share in the Metropolitan Coal Company".

It is clear from this agreement that Gideon had been very successful. He had managed to rise from being an itinerant shoe mender in 1841, the son of a labourer, to being able to invest a considerable sum in buying out Bennett's business in 1873. And he had gone on from there to become the head of a thriving business and the holder of significant other assets by the end of the 1880s.

The 1891 Census and Gideon's death certificate show that he and Mary continued to live above the shop at 19 High East Street until his death in June 1900. Probate records show that he left an estate of £975 (equivalent to about £113,000 at 2016 prices), even after having made over his share of the firm to Gideon Denner.

The 1891 Census and Gideon's death certificate show that he and Mary continued to live above the shop at 19 High East Street until his death in June 1900. Probate records show that he left an estate of £975 (equivalent to about £113,000 at 2016 prices), even after having made over his share of the firm to Gideon Denner.

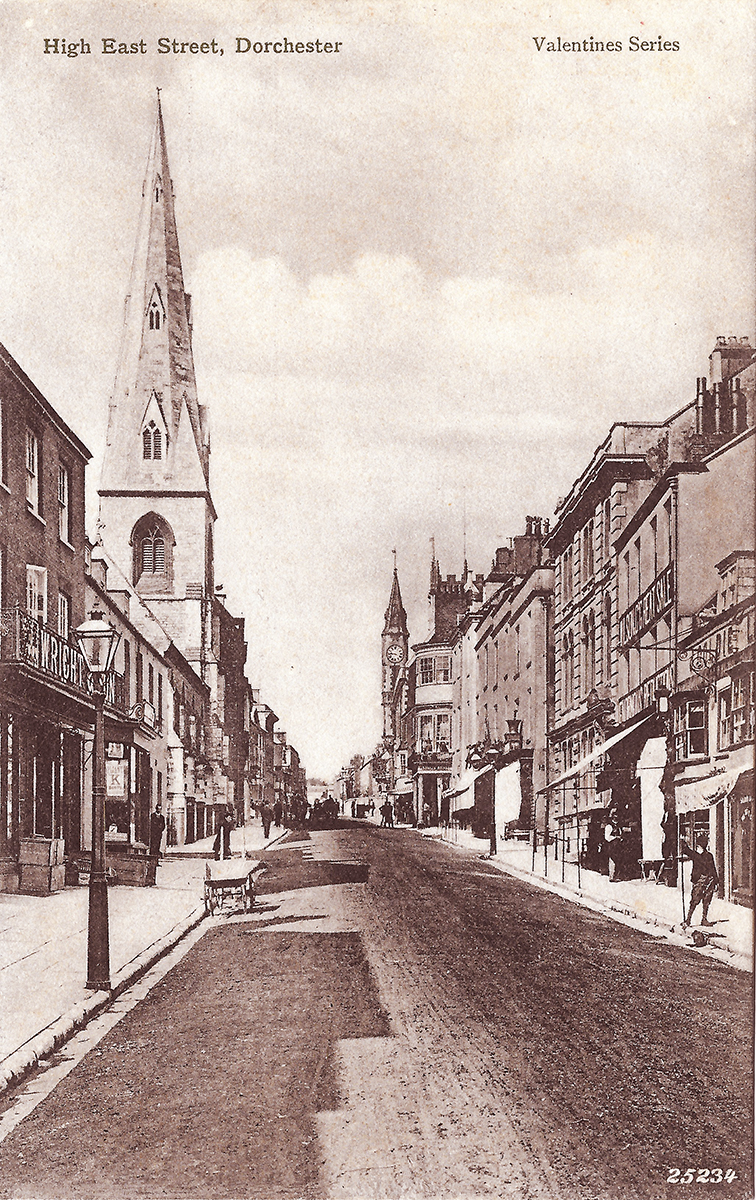

In a postcard of High East Street in Dorchester, left, dating from about 1895, (© Pivate Postacard Collection Michael Russell FIPD) --

the wording "Wright and Son" can be clearly seen on the wrought iron balcony of Number 19 in the foreground on the left of the picture behind the lamp post.

Another picture of High East Street, below, (©from a private collection of original negatives held at Athelhampton House reproduced with the kind permission of Patrick Cooke) --

shows the same section of the street at around the same time. The words "Wright and Son" can be seen clearly on the balcony on the building next door but one to the Phoenix Hotel in the original glass negative (you may however need to use the zoom facility on your browser on this reproduction).

In 1896, Gideon Denner brought Robert formally into the partnership by means of a Partnership Agreement dated 28 October (12) , the main terms of which are at Appendix V. Electoral records from 1899 and 1903 show that, in addition to the shop and premises at 19 High East St in Dorchester, G Wright and Son (by that time Gideon Denner and Robert) were trading in Weymouth at 9 Market Street, on the corner with Maiden Street as "cheese factors". Later, probably in about 1905, Gideon Denner's youngest son, Alfred Denner - known throughout his life as Denner - also joined the business. There is no evidence of any other of Robert's brothers or sisters joining the firm.

Gideon Denner continued to run the firm throughout the 1914-18 war. He died on 27 January 1919, at the age of 74. Probate records show that he left an estate of £7,920/18s/11d - equivalent to about £405,000 at 2016 prices. This was a considerable improvement on his father's estate, although it would have included a part of the value of the ongoing business which Gideon's estate did not include.

Robert was too old to be involved in the 1914-18 war, being well into his forties when war was declared. Denner was not so lucky, however. He joined up in the Royal Fusiliers in 1915 as a Private. Despite twice being wounded in action and contracting malaria in Salonika (Greece), he survived the war (see details at Appendix III). He was demobbed in 1919, just four weeks after his father Gideon Denner had died. It is likely that he went straight back into the family business on his leaving the Forces, to work with Robert in running the business following their father's death.

The firm continued to branch out into new areas under Robert's and Denner's guidance. Kelly's Directory for Dorset in 1923 and in 1927, for example, describes G Wright and Son, still at 19 High East Street, as being "wholesale and retail grocers and provision merchants; home-cured bacon and Dorset dairy produce a speciality (eggs, butter, Dorset blue cheese, fresh pork &c)".

Not much is known about the development of the business from the 1930s through to the end of the Second World War. Douggie's brother Robin trained before the Second World War in accountancy, working in a bank. On leaving school, Douggie went into the business, probably in his mid-teens. Although there is no hard evidence, my understanding is that he was initially apprenticed to be a cheesemaker, probably with a firm in Southampton.

Robert died at the age of 66 in 1936, leaving an estate of £13,588/15/1d (worth around £807,000 at 2016 prices). He was still playing an active part in the business. Douggie was 20 and Robin was 24. At or around this point, the remaining Wrights took up individual roles within the business. Denner became Chairman, Robin Company Secretary, and Douggie Managing Director. Denner must have kept the business going during the Second World War, as both Robin and Douggie were in the Forces. But it was after the war in particular that the business continued to expand and extend its operations in Dorchester and beyond.

By the 1950s, the firm comprised a number of subsidiary businesses within the G Wright and Son "family". These included Wrights of Dorset Ltd, Eggdon Food Products, and Dorset Eggs. I recall from my childhood many of the Wrights of Dorset products: cylindrical packets of golden yellow butter, wrapped in waxed paper; cheddar cheese; hard Dorset blue cheese; bacon, both smoked and unsmoked; hams; sausages; and pork pies - both family sized round ones and larger rectangular ones with eggs running through the middle of them. One could easily have a picnic where all the food, apart from bread and a bit of salad, had been produced in one of the family businesses - and we often did. Perhaps strangely, it didn't strike us as at all odd that so much of what we ate came from packaging branded with our surname.

G Wright and Son focused primarily on the wholesale grocery, with Douggie taking much of the responsibility for growing this side of the business. Sometime after the war, the firm's operations became increasingly cramped in High East Street. So they moved to new custom built premises in St George's Road, Fordington, on land rented from the Duchy of Cornwall. Although the entrance to the site ran between two rows of terraced cottages and was only wide enough for a single lorry to go in or to go out, not both at the same time, the new premises were well suited to a medium scale wholesale grocery business. Manufacturers shipped their goods into the warehouse. G Wright and Son then sorted them into deliveries to local grocery shops, according to their needs.

On selling the shop in High East Street to Dorset County Stores, the firm stopped running its own grocery shops. Instead, it concentrated on developing relationships with independent stores over a wide area of Dorset into which it could sell and to which it could deliver a huge range of groceries. In the late 1950s, many of the stores took on SPAR branding, encouraged by the firm. The concept of branded independents, able to take advantage of the higher purchasing clout of a shared procurement platform, was novel in the UK at the time, although it had been shown to work well in Scandinavia and elsewhere.

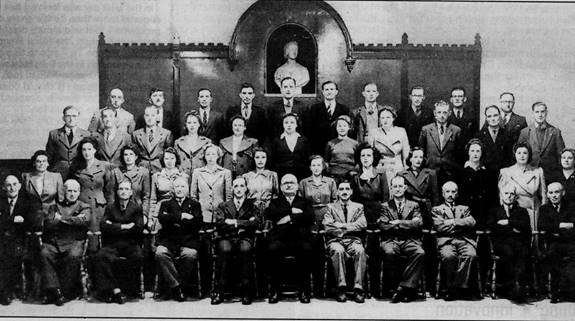

Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, the firm continued to grow. It became, alongside the Eldridge Pope brewery, one of the larger employers in the town. The photograph overleaf is taken from the Dorset Evening Echo of 1 March 2011. It had been sent in by a Molly Gerrard, who is pictured fifth from the right in the second row from the back. The picture was taken at G Wright and Son's Christmas 1950 party for staff and customer representatives, held in the Dorchester Corn Exchange building. Ms Gerrard had worked as a bakery assistant for 25 years in one of G Wright and Son's customer grocery stores, Grey's in Broadwey near Weymouth, and would have been given her invitation by her employer.

G Wright and Son's 1950 Christmas Party. Denner is seated centre, with Douggie

on his left and Robin on his right. [Dorset Evening Echo, 1 March 2011]

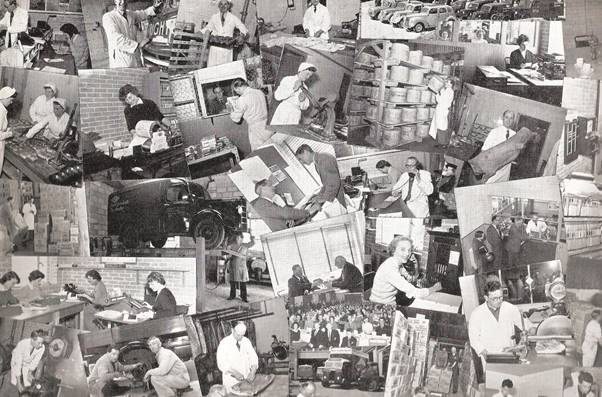

A collage taken from some G Wright and Son marketing material from the early 1950s is shown below. This shows a number of aspects of the business, including the taking of orders from shops, the baking of pies and pastries, invoicing, vehicle maintenance, the stacking of cheddar cheeses in the cheese room, and so on.

The above picture shows Robin (left) and Douggie wearing jackets in the picture towards the centre of the collage. Denner is the bald headed man on the right of the picture below that, seated at a table talking to one of the managers.

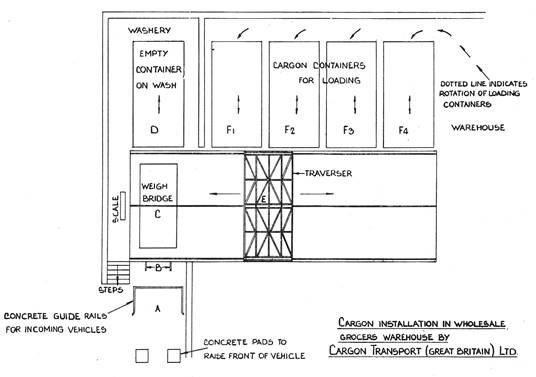

To be successful, the firm needed to concentrate on being as efficient (and as cost effective) as possible a logistics operation. This was Douggie's forte. Among many other innovations that he brought to the business was a new approach to the loading/unloading of lorries. He realised that much of the cost of the business was tied up in delivery vehicles which spent much of their time waiting to be loaded and/or unloaded at the warehouse or at the stores. He therefore set about working out a way in which the body of the lorry could be detached from the chassis, so that only the body would be involved in the time consuming task of loading and unloading.

To be successful, the firm needed to concentrate on being as efficient (and as cost effective) as possible a logistics operation. This was Douggie's forte. Among many other innovations that he brought to the business was a new approach to the loading/unloading of lorries. He realised that much of the cost of the business was tied up in delivery vehicles which spent much of their time waiting to be loaded and/or unloaded at the warehouse or at the stores. He therefore set about working out a way in which the body of the lorry could be detached from the chassis, so that only the body would be involved in the time consuming task of loading and unloading.

The idea took much of its shape on our kitchen table. Douggie had bought some Dinky Toy versions of the then ubiquitous Austin 7-ton lorry (see left). He carefully sawed off the bodies from the chassis and then worked out ways in which the truck could back up to a loading bay, someone could unlock and push the (empty) body off onto rollers and into the warehouse, a new (full) body could be pushed out of the warehouse and onto the chassis, and the lorry could drive off again on its next delivery round. This was the birth of containerisation.

By 1959, with the help of an engineering firm Cargon Transport (GB) Ltd from Tipton, Staffordshire, the models had become a reality (see picture left). This produced a huge increase in productivity (see detail in Appendix VI). One of the consequences of this was that the lorry drivers no longer had to work overtime, and so no longer got overtime pay. Recognising the impact this would have on their families, Douggie arranged that they would be paid by the weight of goods they delivered, so that they could take home the same pay as before - and without having to work the overtime. This dissipated a chunk of the productivity gain, but Douggie's view was that small local businesses had to be good to the people who enabled them to grow.

By 1959, with the help of an engineering firm Cargon Transport (GB) Ltd from Tipton, Staffordshire, the models had become a reality (see picture left). This produced a huge increase in productivity (see detail in Appendix VI). One of the consequences of this was that the lorry drivers no longer had to work overtime, and so no longer got overtime pay. Recognising the impact this would have on their families, Douggie arranged that they would be paid by the weight of goods they delivered, so that they could take home the same pay as before - and without having to work the overtime. This dissipated a chunk of the productivity gain, but Douggie's view was that small local businesses had to be good to the people who enabled them to grow.

Another novel aspect of the containerisation approach was that Douggie had the lorry bodies painted in different colours. They all carried the Wrights of Dorset branding, but as people saw them out and about in different colours they became aware of the containers being independent of the lorries, thereby marking the company out as an innovator in the field. He also placed particular importance on the lorries being regularly cleaned and serviced. The arrangement for the handling of truck bodies in the warehouse provided a washing bay so that the bodies would always go out clean. The firm also employed a small number of mechanics, and equipped its own garage, so that the vehicles could be regularly maintained.

Another novel aspect of the containerisation approach was that Douggie had the lorry bodies painted in different colours. They all carried the Wrights of Dorset branding, but as people saw them out and about in different colours they became aware of the containers being independent of the lorries, thereby marking the company out as an innovator in the field. He also placed particular importance on the lorries being regularly cleaned and serviced. The arrangement for the handling of truck bodies in the warehouse provided a washing bay so that the bodies would always go out clean. The firm also employed a small number of mechanics, and equipped its own garage, so that the vehicles could be regularly maintained.

He regarded it as a matter of principle that a G Wright and Son lorry should never be seen to be emitting smoke from its exhaust, again as a reputational issue for the firm.

This new approach to warehousing distribution attracted quite a bit of attention. There were, for example, articles in specialist magazines such as Garage and Transport Equipment (April 1960) and The Commercial Motor (March 1960). Douggie gave lectures on the process to courses run by the National Federation of Wholesale Grocers, reported in The Grocer of 8 October 1960 (see picture right, note the cigarette!). A number of major supermarket chains, including J Sainsburys, expressed interest in learning more about the concept.

This new approach to warehousing distribution attracted quite a bit of attention. There were, for example, articles in specialist magazines such as Garage and Transport Equipment (April 1960) and The Commercial Motor (March 1960). Douggie gave lectures on the process to courses run by the National Federation of Wholesale Grocers, reported in The Grocer of 8 October 1960 (see picture right, note the cigarette!). A number of major supermarket chains, including J Sainsburys, expressed interest in learning more about the concept.

During the 1960s, Douggie increasingly sought an outlet for the practical side of his interest in the business. Given the chance, he probably would have chosen to be an engineer after his schooldays, rather than to go into the family firm. But he didn't have such a chance. So instead, in the early 1960s he started up with a colleague called Mike Pugson a small business within the G Wright and Son family called Wright Pugson Ltd. This firm was to specialise in producing machinery for the food processing trade, focusing particularly on very high quality stainless steel machinery powered primarily by compressed air.

The business produced a number of novel machines, on at least three of which Douggie obtained patents, for cutting and processing (including vacuum packing) blocks of hard cheese. In the 1960s, most of the pre-packed cheese in the UK had been through a Wright Pugson machine. Wrights of Dorset at one time produced all the individual cheese portions, wrapped in impossible to access cellophane packaging by Wright Pugson machines, for British Airways. Even in 2016, notwithstanding the fact that the company has been bought out a number of times, Marchant Schmitt Ltd of 24 West Larsen Drive, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin 54937 USA, the current owners of the Wright Pugson legacy, manufactures and markets a "Vision Cutting System cheese cutting machine" which carries a Wright Pugson label on the side.

The other particularly notable Wright Pugson (ie Douggie-designed) innovation was a machine for putting the mould into soft blue cheeses. In the 1970s, the marketing arm of the State sponsored Milk Marketing Board, known as Dairy Crest, decided there was a market for a soft blue cheese. To produce this in the volumes they would require, they realised they would have to mechanise the production process. So they approached Douggie for help. He designed a machine that would inject mould into the cheese rounds (each about the size of a Camembert). This worked well, but to get an even blue throughout the cheese, it was important that enough time was allowed after the injection process for the mould to work its way through the cheese. Dairy Crest unfortunately was so driven by what it saw as a quick profit that it got this completely wrong. They consistently pushed the product, known as Lymeswold, out too quickly, with the result that the cheese itself was chalky, and the blue tended to run in straight lines through it, following the line of the needles that had injected it.

The product was a wow for a couple of years. But it rapidly fell foul of the competition from the continent, especially in the form of Cambozola from Germany. And Dairy Crest went belly up. And then, of course, there was no call any more for the machines.

In the mid-1960s, Douggie and Robin began to recognise that there were natural limits to the extent to which G Wright and Son could grow on its own. In particular, they needed a step change in capitalisation to enable them to extend the business beyond the wholesale level to get involved more directly in the retail market. This was a time when the independent grocery sector was coming under increasing competition from the large and growing supermarket chains. If the company was to grow, it needed to be a part of that.

So they started to look around for a partner and lit upon a grocery business on the Isle of Wight called Upward and Rich. Upward and Rich had lots of money, but were constrained (totally) geographically. G Wright and Son had few constraints geographically, but were short of capital. The partnership seemed a natural one. The two firms decided to merge and to seek a quotation on the London Stock Exchange to secure a new source of investment.

After a good deal of negotiation the merged company, under the Upward and Rich name, was floated on the Stock Exchange in around 1968 (13). It is easy to pass this over as a minor detail in the history of the business. In fact, it was a very major achievement for a small family business to have worked its way up to becoming a publicly quoted entity, with shares traded on one of the major world Stock Exchanges.

As part of the deal, Upward and Rich (14) appointed the new Chairman, Robin retired, and Douggie became a Director of the new firm. He carried on for a few years, but was never fully comfortable being part of a larger business. He much preferred to be his own boss.

So in the early 1970s, he agreed with the Board of Upward and Rich that he would leave the business and take with him as part of his severance deal the real apple of his eye, Wright Pugson Ltd. Mike Pugson had left the business some time earlier, so this left Douggie in the position he liked best, running his own show. He moved the business from St George's Road to new premises which he bought on the Poundbury Industrial Estate to the North of Dorchester. And he continued to develop his Heath Robinson style machines and to run the business until he decided to retire fully in 1988. At this point he sold the firm to Mike Whittaker, but he retained the premises which he leased back to the company as a major part of his pension. In many ways this can be seen very closely to mirror the arrangement Gideon had made with Thomas Bennett (to buy the business but to lease the premises) when G Wright and Son had embarked on its first major expansion 115 years earlier in 1873.

By 1974, Upward and Rich had been bought up by the Gateway supermarket chain. In turn, Gateway was bought up by Somerfields. And in due course, Somerfields was taken over by the Coop. That is of course the natural way of the acquisitive and highly commercial world of retail trading. With hindsight, there is a strong argument to say that G Wright and Son actually gave up their independence, very much on terms of their own making, at probably just the right time.

Notes:-

(9) Source Dorset History Centre, reference D108/4(10) From the Douglas Jackman collection of 19th Century bills, Dorset County Museum

(11) Probably Joseph Adams Riggs, the brother of Gideon Denner's wife Susanna. Joseph was a farmer in Piddlehinton. It may be that Gideon had taken an interest in an insurance policy on his life, possibly in exchange for (or as a guarantee against) a loan. At different times, Gideon Denner's sons Reg and Charles went to go to live with Joseph Riggs and his sister Emily in Piddlehinton, where Charles in due course became an Assistant Farm Manager.

(12) Now held in the Dorset Records Office under reference D-2747, accession 10230a

(13) It is surprisingly difficult to find historical information about the company. There appears to be no systematic record keeping on commercial births and deaths, unlike personal ones. Corporate history, it appears, is almost entirely ephemeral.

(14) One of the things that amused Douggie about Upward and Rich was its telex address - UPRICH. When the ink was running low in the telex machine, the H could easily be misread as a K.

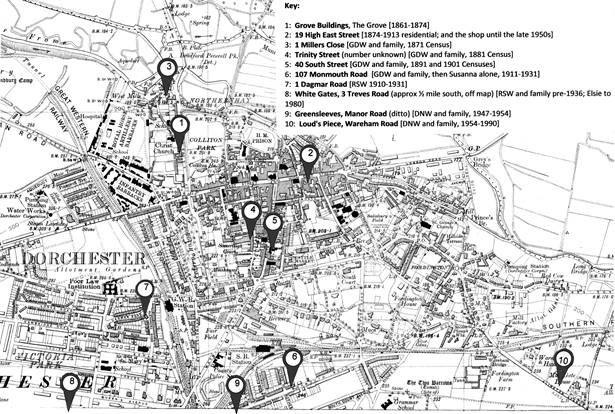

The Wrights had a home in Dorchester for over 200 years - from at least the time of John Wright, Gideon's father, in the late 1780s until Douggie moved to Marnhull in North Dorset in 1990.

They lived in a number of different houses. Gideon is first recorded in Grove Buildings, Fordington, in 1861. He then moved from there in 1873/74 to live above the shop in 19 High East Street. In the meantime, Gideon Denner and Susanna had moved to 1 Miller's Close, where he was by the 1871 Census, and then had moved again by 1881 to an unspecified address in Trinity Street.

In 1879, Gideon and Elizabeth were the victims of a burglary, as reported in the Police Gazette of Monday 3 November 1879:

-

"During the night of 27 October 1879 the house of Mr G Wright, High East Street, Dorchester, was entered and the following property stolen therein: about £4 worth of postage stamps, £4 in silver with a little gold tied up in a linen bag, £3 in coppers and 4 shillings to 5 shillings in threepenny and fourpenny pieces. Information to Head Constable Coward, Borough Police Station, Guildhall, Dorchester."

Gideon remained at 19 High East Street until his death in 1900. Mary Wright, Gideon's second wife and Gideon Denner's stepmother, continued to live above the shop in High East Street until she died in 1913.

It is said that Gideon left Dorset only once in his life, to go to the Isle of Wight. He so hated what he saw that he came immediately back on the same ferry, returned to Dorchester (presumably on the train) and swore that he "would never go abroad again".

At the 1891 and 1901 Censuses, Gideon Denner and the family were living at 40 South Street. William Wright describes it in his book as follows:

"We lived in South Street, at No. 40, to be precise. This was a large house which, at one time, had been a school, in which William Barnes the Dorset poet had been a teacher. Consequently, attached to the house was a large schoolroom which was reached by a covered way leading from the nursery across the roof of the kitchen. This corridor we called the Bogey Passage."

"At the end of the Bogey Passage was a small room equipped with several shelves and which, in years gone by, had probably served as a master's study. A flight of stairs led from this to the classroom which, being large, provided an excellent playground."

By 1911, Gideon Denner had moved with Susanna to "Heath View", Maumbury Way where he remained until his death in 1919. (Alfred) Denner's army records show him as living at this address when he joined up and it appears to be the address he returns to after the war. This is a bit confusing as by 1924 (15) he is recorded as being at "Heath View", Monmouth Road. This is further identified as being number 107, the middle of a small Victorian terrace. Susanna is recorded as living here in Monmouth Road at her death in 1931. It is not clear whether the road had been renamed, or whether Susanna and Denner had moved house from Maumbury Way to Monmouth Road, taking the name of the house with them.

Robert was born at 1 Millers Close and lived through his childhood and early adulthood with his parents, first at Trinity Street and then at 40 South Street. Following his marriage in 1910, he and Elsie moved to 1 Dagmar Road, a large Victorian villa behind the Great Western Station where they were when Douggie was born in 1916.

Robert and Elsie continued to live at 1 Dagmar Road until at least 1931 (16). At some point between then and when Robert died in 1936, they moved to White Gates, Treves Road (17) , to the South West of Dorchester, overlooking Maiden Castle.

Elsie married Eric Tabor in 1953. At some point, possibly during the war, White Gates was converted into two flats. Elsie, and then Elsie and Eric, lived in the first floor flat. Later, after Eric died in 1964, Elsie had a new house built in the garden. She appropriated the name of White Gates for this new house, although at some point the house became officially number 3 Treves Road, the original White Gates, now restored again to a house rather than two flats, becoming number 5.

Douggie married in 1944. Douggie's identity cards show that he and Nora were living at White Gates in June 1946, then at 2 Albert Road from 24 September 1946 to 21 March 1947, when they moved back temporarily to White Gates. Caroline was born on 2 April 1947. Then on 24 June 1947, they moved to "Greensleeves", the house they had bought on Manor Road, about half a mile away from Elsie in Treves Road. I was born here in 1951.

Then in about 1954, Douggie and Nora moved to "Loud's Piece", on the Wareham Road (now formally known as Alington Avenue), Dorchester. [Nora's mother told the story that she had on one occasion asked a policeman in Dorset, "which is the way to Wareham?", and he had replied "Put 'em on in the morning, Madam, and keep 'em on". ]

The house was so named because it was built on a piece of Mr Loud's land - the same Mr Loud that gave his name to Loud's Mill (still standing) on the river Frome at the end of St George's Road. The house had been designed and built by the Head Curator of the Dorset County Museum in the 1930s. It was just a field away from Max Gate, the house that Thomas Hardy designed and lived in for the latter part of his life. Douggie was to live here for the next 36 years with Nora, and later with Hazel, until he and Hazel moved to Marnhull in North Dorset in 1990.

The map overleaf shows how far the family moved in the 200 years before Douggie moved to Marnhull in 1990.

Notes:-

(15) Dorset Year Book, 1924(16) see Kelly's Directory for that year

(17) the address given on Robert's burial record. His ashes are at St Georges Church, Fordington.

Douggie got engaged to Nora Hermoine (18) Hatton-Jones in the spring of 1944. Nora was serving in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (known as "the Fannies"), see picture below.

Nora was based at Tangmere Aerodrome in West Sussex. Her job was to teach morse code to British and other allied agents in the Special Operations Executive (SOE) who were to be dropped behind enemy lines in France and elsewhere to report on and disrupt the German war effort. She and her colleagues were also responsible for receiving and recording messages from these agents. This acted as a safety check insofar as the FANYs had become very familiar during their training with the morse equivalent of the "handwriting" of individual trainees, so they could tell instinctively whether it was the expected agent or someone else sending the messages they were receiving.

Nora was based at Tangmere Aerodrome in West Sussex. Her job was to teach morse code to British and other allied agents in the Special Operations Executive (SOE) who were to be dropped behind enemy lines in France and elsewhere to report on and disrupt the German war effort. She and her colleagues were also responsible for receiving and recording messages from these agents. This acted as a safety check insofar as the FANYs had become very familiar during their training with the morse equivalent of the "handwriting" of individual trainees, so they could tell instinctively whether it was the expected agent or someone else sending the messages they were receiving.

Nora made the mistake of falling in love with one of her trainees. She was devastated when she was later receiving a message from him from France which was cut off abruptly in mid-flow. He had apparently been caught by the Germans red handed sending back a report to Tangmere.

Nora married Douggie (in her own words, "on the rebound") on 6 October 1944 in Bersted, Sussex. All else apart, this meant that she could leave the FANYs and remove herself from the risk of history repeating itself. Pictures of them on their wedding day (Lieut DN and Mrs NH Wright) and probably shortly after the end of the war are shown right and overleaf. Note in the second photograph the cigarette in Douggie's hand.

On 9 January 1946, Nora gave birth to their first child, a son Robert Christopher. She had gone home to her parents for the birth in Bognor Regis. Douggie appears to have been in Germany with the Dorset Regiment at the time, and there is no evidence of his having been able to take leave to be home for the birth or immediately after it. Sadly, Christopher (as he was to be known) was born with some form of deformity. He survived only nine hours. He is buried in Bognor Regis Cemetery.

On 9 January 1946, Nora gave birth to their first child, a son Robert Christopher. She had gone home to her parents for the birth in Bognor Regis. Douggie appears to have been in Germany with the Dorset Regiment at the time, and there is no evidence of his having been able to take leave to be home for the birth or immediately after it. Sadly, Christopher (as he was to be known) was born with some form of deformity. He survived only nine hours. He is buried in Bognor Regis Cemetery.

On his return from Germany and his demobilisation from the Army, Douggie and Nora lived initially with his mother at White Gates. They then moved to rented accommodation at 2 Albert Road Dorchester from 24 September 1946 to 21 March 1947, when they moved back temporarily to White Gates. Nora was by this time again heavily pregnant. This must have been a very worrying time for them both as they had been told on Christopher's death that they would never be able to have a son that would survive. Nora was by her own account very unhappy to be pregnant again so soon, and petrified that she would give birth to another boy. In fact, their fears were unrealised, and Caroline, healthy and fit, was born in Dorchester on 2 April 1947.

On 24 June 1947, they moved to "Greensleeves", a small 1930s house (now almost three times the size that it was then) that they had bought on Manor Road, about half a mile away from Elsie in Treves Road.

Douggie got back into the family business. He also got together with a group of like-minded business friends including accountant Maurice Edwards, car dealer Paul Channon and builder Bob Ricardo, to set up a Dorchester branch of the Round Table organisation. Its first meeting took place on Tuesday 21 April at the Antelope Hotel. Douggie was its first Chairman.

By this time, I had been born, on 2 March 1951, at home at Greensleeves. The story went that the midwife who was attending the birth was apparently rather inexperienced. On realising that things were coming to fruition, she rapidly absented herself to get hot water and clean towels, leaving Douggie to deliver me. Fortunately, the doctor arrived at the same time, as I was born with a caul. This is very rare, and deemed to be very lucky. It is where, in one in 80,000 births, the baby's head is covered by the amniotic sac. It is very easy to deal with - simply a matter of removing the sac from the head - but it is lucky that the doctor was there to do it, as it is unlikely I'd have survived without immediate action being taken to enable me to breathe. It was said that Douggie suffered from piles for weeks afterwards from the shock of being so intimately involved in my birth.

Although doubtless there were concerns, given what had happened to Christopher, I was pronounced to be obviously a boy and fully healthy in all respects. [That said, I have had to have an aortic valve replacement at the relatively early age of 62, which suggests a congenital malformation of the heart. This leaves open the possibility that Christopher had some sort of heart problem - but no-one will ever know.]

In 1954, Douggie and Nora bought Loud's Piece for £4,500. And that is where they brought up both Caroline and me over the next 20+ years. A picture of Douggie and Nora, taken at some sort of formal dinner (possibly Round Table, given the badge in Douggie's lapel) from about this period is shown below. Again, note the cigarette, this time in Nora's hand.

Over time, they completely remodelled the house. A hard tennis court was built. And a small heated swimming pool was dug. Walls were removed (to turn a small playroom and next door dining room into a larger dining room, to extend the sitting room, to turn two small bedrooms into a larger master bedroom with, in due course, an en suite bathroom, and to carve a further guest bathroom out of what had previously been a box room). As we grew, the house seemed to grow with us.

Over time, they completely remodelled the house. A hard tennis court was built. And a small heated swimming pool was dug. Walls were removed (to turn a small playroom and next door dining room into a larger dining room, to extend the sitting room, to turn two small bedrooms into a larger master bedroom with, in due course, an en suite bathroom, and to carve a further guest bathroom out of what had previously been a box room). As we grew, the house seemed to grow with us.

Caroline and I were sent to boarding school. Caroline was found to be "a bit difficult" and changed schools from time to time. I went initially to Perrot Hill School near Crewkerne, and then on to Canford School near Wimborne.

Nora was heavily involved in riding. She had a series of horses of her own most of my childhood, all of which seemed to have problems of one kind or another, either physical or behavioural. She kept her horses at the livery stables at Fordington House which were run by Lionel Barnes and his wife Ena. Lionel was very much larger than life both physically and in his character. He had served in a (horse) mounted company with the Dorset Regiment in Egypt in the First World War and was a great fund of now largely forgotten anecdotes about his experiences. He used to walk from his house on Fordington Green to Loud's Piece every Sunday morning where he'd sit in our kitchen and drink a couple of neat gins to fortify him for the walk back, usually via a quick one in The Bull at the bottom of Fordington Hill.

In exchange for reduced livery fees for the horse, Nora would give riding lessons at the stables and take people out on rides. She also one year entered the Three Day Event championship in the Dorchester Show, involving cross country riding, dressage, and show jumping. She didn't do very well, but it was quite an achievement even to be able to qualify even to enter the competition. She had something of a reputation with one horse for hacking out to the Wise Man pub in West Stafford where she'd have a couple of her favourite drinks (whisky and cider - known in the west country as a stone fence, because "if you hit it you really know about it") and the horse would be given the ullage from the beer trays. Both of them would make their way home slightly the worse for wear.

One summer in the 1950s, Douggie and Nora and Lionel and Ena boxed four horses down to Porlock in Somerset and rode back over several days to Dorchester, stopping off to stay in pubs on the way. It was probably about the last time it was possible to find enough pubs with stables and/or fields in which the horses could stay overnight to make such a trip possible.

Douggie was very keen on Spain, no doubt partly because of his experience of the country during the war. He took the Spanish edition of the Reader's Digest monthly to improve his language skills. He and Nora used to travel there for two or three weeks most summers, either flying down or driving down through France [which must have been quite a trial as, at the time, Nora didn't drive]. I recall his being very impressed one year when something went wrong with the innovative "fluid flywheel" clutch on the Lanchester car they were driving. The mechanics in a local Spanish garage, who had clearly never seen such a thing in their lives before, managed to strip it down, fix it and rebuild it overnight.

Caroline and I weren't involved in these trips which usually but not always occurred during term times. But I do remember very many happy breaks with Nora's parents in Bognor Regis, especially with her mother (Henrietta, but known to everyone for some reason as Toots).

Douggie also in the early 1960s decided he wanted to learn to fly. He went for many lessons and became very competent. But in the end he was refused a pilot's licence because of his eyesight. I recall him being very fed up about this.

All in all, Douggie and Nora had a pretty comfortable life. They weren't wealthy, but they were well off and they wanted for little. They had good holidays, they could afford to send their children to boarding schools, they had all the material goods that were available and they had a marriage that, despite its occasional rocky moments, was generally pretty sound.

Then in 1969, they experienced a major disruption to the planned pattern of events. Caroline had left school at 16 (in 1963) to go to drama college - the Arts Educational Trust - in London. She was a good actress. But like most actresses, she found it difficult if not impossible to find work. She mixed with other struggling artistes and at the age of 20 found herself pregnant. The father was another out of work actor called Keith Bowles. They married. Their daughter, Penelope Judith, was born in 1967.

For a while they stuck together trying to bring up the baby. But then Caroline left, leaving Keith with Penny. He too struggled on for a year or two, but eventually was unable to continue to provide for her. In the summer of 1969, he rang Douggie and said he was going on holiday for three weeks. He'd leave the child at Bournemouth Station, and would be grateful if Douggie and Nora would be good enough to pick her up and look after her till he got back.

For a while they stuck together trying to bring up the baby. But then Caroline left, leaving Keith with Penny. He too struggled on for a year or two, but eventually was unable to continue to provide for her. In the summer of 1969, he rang Douggie and said he was going on holiday for three weeks. He'd leave the child at Bournemouth Station, and would be grateful if Douggie and Nora would be good enough to pick her up and look after her till he got back.

They didn't hear from him for three years. Caroline had no interest/means to look after her. So Douggie and Nora took her on, sending her to nursery and then infant school in Dorchester and bringing her up generally as their own. Douggie was 53; Nora was 45.

Sometime during the next few years it became accepted as fact that Douggie and Nora were going to bring Penny (known as Pebble - because she had to be convinced she wasn't the only Pebble on the beach ) up. So they got on with it.

Until on 24 February 1974, Nora suffered a massive angina attack while out walking the dogs on a sparklingly sunny spring morning. And dropped dead. The last picture of her and Douggie, taken at a wedding the week before she died, is shown left.

Notes:-

(18) Nora's second name (Hermoine rather than Hermione) comes apparently from a spelling mistake made by her father on her Birth registration form. In the 1960s she changed her name by Deed Poll to avoid having repeatedly to correct official documents to make them appropriately wrong.(19) There is an alternative version of this rationale which made itself into the Telegraph letters pages many years later. A teacher wrote in, in connection with a run of correspondence about amusing children's names, to say that he had taught some years earlier a girl who was known as Pebble "because, he'd been told, she had been conceived on Chesil Beach".

Douggie was hopeless on his own. Like most men of his generation, he couldn't cook. He survived on boiled eggs and Marks and Spencers ready meals. Even then, he struggled. Despite this, he felt very strongly that he had a continuing responsibility to look after Penny if her own parents were unable to do so.

Penny was spending the working week living with the Sibleys in Icen Way, Dorchester. Mrs Sibley had for some time been Douggie and Nora's cleaner; Mr Sibley was a fireman. She went to Loud's Piece for the weekends. I went home from university in Southampton every other weekend to help. But these arrangements were not really sustainable in the long run.

Douggie found himself spending increasing amounts of time with Hazel Southcombe, one of Nora's closest friends, who lived in Weymouth. Hazel had been widowed the year before. Towards the end of May, about twelve weeks after Nora had died, Douggie told me that he and Hazel had decided to marry. They married on 16 September 1974 at Weymouth Registry Office. A picture of them from around that time, at Lulworth Cove, is shown below.

Theirs was a marriage fortunately based very much on love and mutual respect. It was absolutely not a marriage of convenience, although it was in practice very convenient insofar as it enabled Douggie to continue to look after Penny. Hazel had had no children of her own. She was pretty heroic in agreeing, at the age of 45, to take her on. Penny, for many obvious reasons not least the fact that she was being brought up by people old enough to be her grandparents, was not always easy.

The alternative for her, though, would have been a children's home.

Douggie and Hazel continued to live at Loud's Piece, with Penny. Being much older than the parents of her contemporaries, they couldn't offer her much of a normal home life, so they paid up to send her to boarding school. And at the age of 16 she decided that she wanted to be an actress. So they put together the money to send her to drama school. Douggie's mother, Elsie, died in 1980.

In 1983, I married Jane Augier at Stourton Church in Wiltshire (see picture overleaf). Penny was a bridesmaid. Jane and I later went with my work to Hong Kong for three years (1985-1988). In 1985, our first son Edward (Douggie's first grandson) was born. He died after four days, having contracted an infection in hospital. In 1987, Hannah was born in Hong Kong. On our return to the UK, Charlie was born in 1989, and Becky in 1991.

L-R, Penny Wright, Ian Gordon (best man), Douggie, Hazel, Rob, Jane, Diana and Ashley Augier (Jane's parents), Alex Bridcut (bridesmaid)

After Penny had left home and Douggie had sold Wright Pugson in 1988, Douggie and Hazel concluded that Loud's Piece was really too big for them. Douggie wasn't keen on staying in Dorchester; he thought it was too big to be a comfortable place in which to be retired. So in 1990, he became the last Wright to leave Dorchester when he and Hazel moved to Marnhull in North Dorset.

Douggie threw himself enthusiastically into local activities. He and Hazel actively supported local charitable fundraising events for many good causes and for the Conservative Party. Douggie had been an early adopter of personal computing, and he kitted himself out with a high quality computer and printer on which he made up and printed a wide range of publicity material for local charities. He became a member of an informal share buying group (the Shottsford group). He took on for several years the task of finding speakers for the monthly meeting of a local Probus group (largely made up of retired "professional and business" people).